By Chris McGrath

The man who plants a tree knows he may never enjoy its deepest shade. But he still gets much in return: above all, a length of perspective that can absorb success and failure with the same, dispassionate sense of their transience. You could ask no better mindset of a horseman. And, sure enough, a Thoroughbred could wish for no better environment than the farm that shares its site with–and owes its name to–the oldest arboreal nursery in Kentucky.

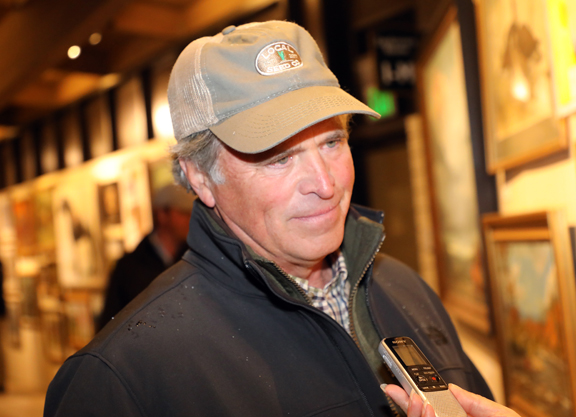

True to its heritage, John Mayer presides over the mares and foals of Nursery Place with the same temperate hand that he applies to the planting of saplings, over two centuries after the birches sown by its founders, or indeed to the patient building of stone walls in midwinter–the only window in a calendar dominated by the perennial cycles of foaling, prepping and sales.

“So I lay rock in the snow,” he says wryly. “It's kind of nice. The quietness, the concentration, the way the weather can slip up on you…”

His son Griffin remembers being made to help with the planting of trees as a kid. Now his own children climb on them. That's one measure of this very special family enterprise: a place of unhurried sensitivity to the rhythms of Nature, from the buds of springtime to the weaning of foals, while also fully attuned to the imperatives of the 21st Century bloodstock market.

The Mayers–Griffin's brother Walker is also integral to the team–had a wonderful 2019 at Keeneland. Their small November draft, comprising just three weanlings, achieved the highest average of the entire auction: a $500,000 Kitten's Joy colt; a son of Ghostzapper that made $395,000; and a Munnings filly sold for $395,000. The half-dozen yearlings they targeted at Book 2 in September, equally, put all the big, glossy brands in the shade. Each made six figures, for an aggregate $1.94 million, headed by a $900,000 Quality Road colt.

He was out of a typical Nursery Place mare in Hot Spell (Salt Lake), bought for $85,000 at the 2015 January Sale and owned in partnership by John, Griffin and Walker; their uncle Happy Broadbent; and friend Logan Voss. It was equally characteristic, however, that John Mayer was reluctant to be featured by TDN in the immediate afterglow of those successes. Not that there's anything reserved or discouraging about this relaxed, rather dashing figure, lolling in his office chair. It's just that he knows the Thoroughbred to be the ultimate tutor in humility, and has due distaste for the conflation of luck with genius.

It is men of this reflective, understated stamp, however, who reliably yield the most profound insight. You can wager that more would be learned in a single morning, following John Mayer through the Kentucky River Palisades, among creeks and forest and cliffs, than from a fortnight with the braggarts of the Keeneland pavilion bar.

“I don't know how that happened in September,” he says with a shrug. “Things just lined up. I mean, yes, everybody worked really hard. But it was just a group of really nice horses that we managed not to screw up. There's not a right way and a wrong way. There's just a way we want to do it. But those good horses, they're gifts. Plain and simple.”

Nonetheless the fact remains that more industrial operations could never function like Nursery Place. For one thing, it's labor-intensive even by the standards of our unusually cumbersome industry, and duly contingent on the loyalty and commitment of its long-serving staff. Griffin reckons to lose 10 pounds of winter waistline every year, by hand-walking yearlings.

Around a quarter of the foals–from a roster of around 40 mares–tend to be sold either as weanlings or short yearlings.

“Because truthfully, the way I want to do it, I don't want to prep more than about 30 yearlings,” John says. “Other people can prep a lot more. Don't ask me how. I don't want to know. We're really blessed to have this pool of help, families that have been here for 25, 30 years. Everybody knows what's coming in April, or May, or June.

“I don't consider myself a real bright guy. I'm a paint-by-numbers guy. Like Dec. 1, the maidens and barrens are under the lights. [In a normal year] Apr. 15, if we're going to Saratoga, those horses are starting to walk. By May 15, the September horses are starting. The babies, Aug. 1. The sun's going to come up over there in the morning, it's going to go over, and go to bed over there at night. So, you don't wait until you have to sign on the dotted line. You just get started. Because if you go early enough, you're not under the gun if you get a problem.”

Every farm claims attention to detail, but things just can't be done quite this way except at a place like this. Griffin says that nothing vexes his father like those rare occasions when forced to delegate the dawn feed round.

It's an environment that develops tone and agility by imperceptible increments. The pasture, for instance, is expansive and undulating; and the walking machine is kept to a minimum. A hand-walked yearling, the Mayers argue, is a very different specimen from the robot honed by the numbing routine of the machine or pool. Again, it's all about patience: another stone in the wall.

“When they're out there on the end of the shank, at the sale, they just drop their heads,” Griffin explains. “Horses on the machine, you'll see them a little more… You wouldn't say tight, but…”

“A little choppy,” suggests John.

“Yeah, and they don't have the depth of hip or gaskin of a hand-walked yearling. And when you swim a horse, you get all the muscle you want–but he's been swimming. So what about when you're running over the ground and hitting that surface?”

They are wary, too, of the mental impact of the machine.

“Hand-walking, you're building a trust relationship with the guy who's going to go out there and show the horse,” Griffin says. “We start at the beginning of the summer: 'Who's going to be on this guy? Who would get along good with that filly?'”

This literal “hands-on” quality extends to the farm's own grass bedding, around 9,000 bales a year. In the middle of the prep season, for three weeks, there's hand-walking all morning and then baling grass all afternoon.

“It's tough for everyone,” Griffin says. “But the longer they've been here, seeing how the wheel turns and what the results are, the more it makes sense to them.”

Yes, of course, they have colics; but far fewer than on straw. The fields benefit, from the rotation; and a lot of mares would rather browse their bedding than finish hay imported from Ohio.

Seeing the Mayers share in all this labor doubtless helps to knit team spirit. But then John Mayer was raised to match words with deeds. His father was a Colonel in the Marines, for one thing, while the family's roots in this soil go back to pioneering days. They came out of Virginia in 1792. One brother built a red timber cabin, still standing, another established the house where Griffin now raises the next generation.

John's grandfather raised cattle, hogs, sheep, corn, tobacco. He was also a Master of Hounds for 40 years in glorious hunting country. But gradually the foxes were moved on by coyotes, the city limits began seeping outwards and “pretty soon the farmer didn't have anything to sell but his land.”

Today Nature's precarious hold on the Palisades must be jealously defended, tree by tree, against suburban development. But the fragmentation of the original estate has been arrested and even reversed, somewhat, with the 600 acres of Nursery Place now encompassing an adjacent tract salvaged against development.

It was not until John came back from college, about 40 years ago, that it became a pure horse farm. Even then, his sense of vocation was gradual. There had been the foxhunting, as a kid, but his father's military approach to equitation had taken some of the fun out of riding.

“He had trained with the French Olympic team,” recalls John. “He was very disciplined and that's the way we were taught to ride: forget the reins, forget the stirrups, use your knees, lean. But I talked to Mr. Boone, who owned Wimbledon, and said we had this land out here. I didn't necessarily know I wanted to be in the horse business. I just wanted to stay on the farm. And he said, 'When you get out of school, come here and work under Ted Bates.'

“At that time they were probably foaling 150 or 160 mares. They had this Wall Street money coming in, they had Relaunch and Sensitive Prince and Tim The Tiger in the breeding shed. It was spectacular. I remember going over to Creekview and getting the dam of Mt. Livermore. Ted was very quiet, but a really nice man and a good teacher. Though his damned poodles… The smell of that car! Anyway, like a young, dumb S.O.B., I left after six months. Said, 'I got this.'”

He came back and converted an old hunters' barn built into the side of a hill. The next phase of his education, being based on trial and error, really would require him to be a fast learner.

“The stove is hot,” says John with a grin. “I did touch it three or four times before I figured it out…”

Numbers got “stupid” at one point, and there were various failed experiments. What did work, however, and for a long time, was a program of buying or claiming racemares whose pedigrees were heating up, to sell on with a commercial cover. But the turnover was exhausting, and John finds that pedigrees today have lost definition. In the old days, marquee stallions would seed marquee families.

“You could easily identify them,” says John. “But now it's getting pretty tough, because they're coming out of nowhere, anywhere.”

That has duly become a lesser part of the program, and the boarding of mares has largely been phased out too–even though Paul Robsham kept Pretty Discreet (Private Account) on the farm, and she delivered two Grade I scorers in Discreet Cat (Forestry) and Discreetly Mine (Mineshaft). Nowadays, the game-plan is to have a little skin in the game.

“Look, I admire these guys that can make a great living boarding horses in large numbers,” says John. “But I just don't want to do that. When you get to a certain number, that's what it is. A number. It's no longer a horse. It's just a revolving door.”

As it is, the Thoroughbred saplings of Nursery Place reliably tend to take root and bloom on the racetrack. That's obviously been trickier than normal, this spring, albeit Linny Kate (Tonalist) won her only start at Gulfstream and another farm-bred, Taishan (Twirling Candy), has been rubbing shoulders with some of the leading sophomores. Everyone is looking forward, meanwhile, to the return of Selflessly (More Than Ready). Consigned as a yearling, she broke her maiden in the GII Miss Grillo S. before running a close fifth in the GI Breeders' Cup Juvenile Fillies' Turf.

Understanding the market as they do, last year the Mayers sent around half the mares to fashionable new stallions. But they do at least try to prove young mares with established sires, and vice versa.

“I do think that the stakes-producing mares have an air about them,” John suggests. “I know that sounds crazy–but there's 25, 30 of them on the farm now, and you can kind of pick them out. They may not always be correct, but the mechanics are there, the walk, the balance. And I do think there's something about the way they carry themselves.

“Though one of the best mares we ever had was crooked as a snake. I bought her as a yearling, crooked, but it was one of W.T. Young's families I was dying to get into. She never did make it to the races, but she was very fast. And her second foal was Wiseman's Ferry (Hennessy).”

He became the sire of Wise Dan, whose trainer Charlie LoPresti has served the Mayers well–not just as trainer of the occasional retained filly, but also as mentor for Walker's racetrack apprenticeship.

“You got to love it first,” stresses John. “I've tried to tell both boys, if you're doing it just for the money, you need to do something else. Because while I don't perceive it as hard, it is every day and obviously there are a whole lot more lows than highs. But you kind of find something… It's not just going to Keeneland, or Saratoga. You can just love the getting up in the morning, and being tired at night. Because, like I said, these good horses are gifts.”

That lesson has not been wasted on Griffin.

“It's those little wins,” he says. “A mare in foal. A live foal. It's a great feeling when you have a foal, and everything goes right, and we wait 30 minutes and it gets up. And you walk out the barn, and look at the stars, and you're like, 'Here I am. It's the middle of the night. But I'm happy.'”

So let's put it to them this way. When your life is your work, and your work is your life, it doesn't mean you're working all the time. It means you're living all the time.

“Pretty fair statement,” says John. “There's a lot of ways to skin a cat. And this is just a way that works for us. And, yes. It's a way to make a living from a way to live.”

Not a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the daily PDF or alerts.